I've been thinking about making friends with my mind.

In the working-class family I was raised in school was a necessity but certainly not a priority. I did well enough through elementary school but when I got to algebra in middle school and biology and geometry in high school my study habits fell victim to my cravings for friendships and basketball and whoever was or I wished would soon be my girlfriend. I graduated with a C grade-point average. Before transferring to UCLA, I spent two years at Cal State Los Angeles learning how to study and learning just how much I didn't know what I was doing academically.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

Outside the classroom, I felt great about myself. I had a wonderful girlfriend who brought me lunch every day from her sorority’s kitchen, I set a UCLA intramural basketball scoring record, I had a pack of friends, and I was educating myself out of my family's working-class background. But sometimes - especially in academic classrooms or conversations - the distance I still had to climb remained starkly apparent. Though many of my friends at UCLA didn't work, I was a custodian at the church, a clerk in the campus bookstore during the week, and bagged groceries at a Safeway market on the weekends. I barely got the assignments done for my eighteen units of classes and felt delinquent that I did so much less extra reading the way the better students among my friends found time to do.

By the time I graduated from UCLA I was a B+ student but still keenly aware of my own shortcomings, although not entirely sure what to do about them. Maybe it wasn’t true, but it was my sense that my friends and my girlfriend had very different experiences of college from mine.

Stuart Hall, Princeton Theological Seminary

I knew from the time I was twelve years old that I was called by God to be a Presbyterian minister, so I applied to and was accepted by Princeton Theological Seminary. The first morning Becky and I arrived on the Princeton campus one week after our wedding, we met Mike in the lobby of our new dorm and asked him to join us for breakfast. He too was an entering first year student; I asked about college, he said he’d graduated from Harvard, and I knew immediately that I was screwed: there was no way I could compete with this kind of educational pedigree. I was certain that I wasn't smart enough, and terrified that soon friends and faculty would realize it as surely as I did.

Through college and seminary, I felt like a cultural misfit. My father sold newspapers on a Hollywood Boulevard corner while my classmates fathers' ran Hollywood studios or New York businesses, or were physicians, lawyers or pastors. I knew in my gut I didn’t belong; it was a class thing, and I was from the wrong class. This lingering sense that I was under-educated and lacked cultural credentials pushed me to work my ass off to make up for these deficits.

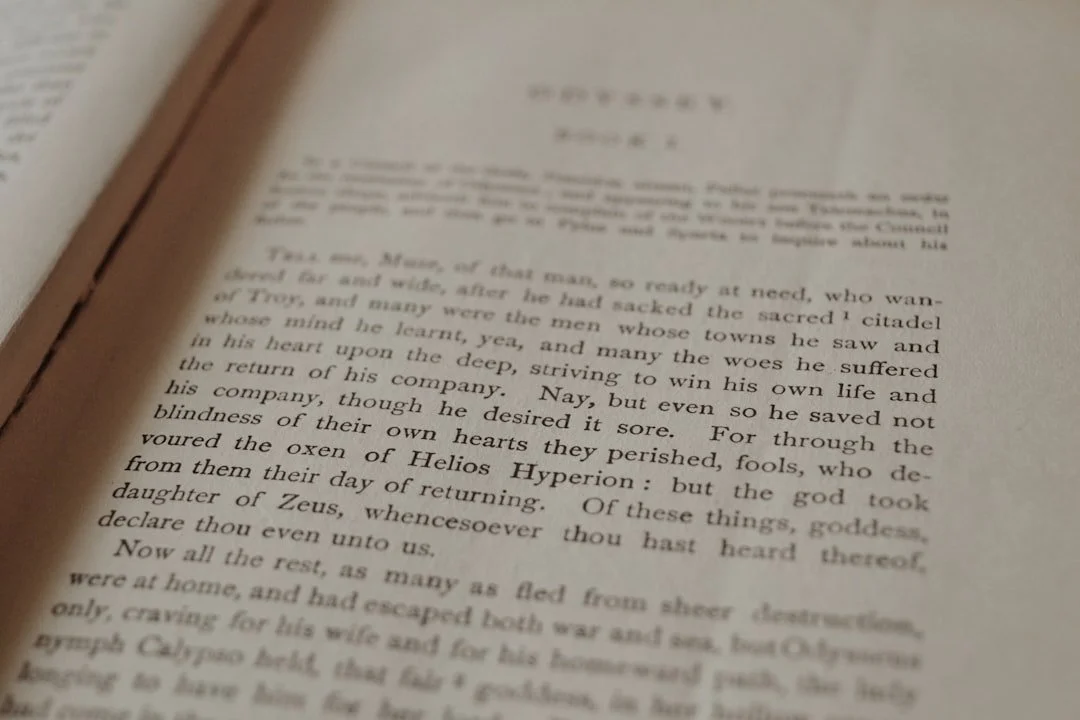

I reminded myself throughout those years that no matter how much better I was doing in school, I hadn’t yet read The Iliad or The Odyssey. I was working to pay my way through school and had little discretionary reading time; but more ominously, I felt ill-equipped to take on these and other ancient, enduring masterpieces. Just like Mike’s Harvard degree, they would demonstrate that I didn't belong in their pages. This fear stood vigil over my reading choices until I was in my forties when, in a burst of daring, I spent two years reading for the first time many of the Roman and Greek poets and playwrights, including both of Homer’s epics.

Strangely, it was not a professor nor a mentor nor wise authors who taught me to trust my ability to think; it was a therapist. For nearly two decades, from my late thirties through my late fifties, Susan sat with me every week as I wrestled with these unrelenting demons. Her patient attention eventually had its effects. In one session near the end of our years together I told her about a situation which I’d managed to fight my way through, resisting my eruptive impulses. I guess I’m surviving, I said. Surviving? You’re not surviving, Rick. You’re thriving. It sounded like a foreign language. This woman who knew me deeply saw someone who was no longer climbing out of a deep hole or at risk of sliding back down into it, but someone who was in fact succeeding. Thriving: I had never thought of myself that way.

During our years together, I read Toni Morrison’s 1987 Pulitzer Prize novel, Beloved. Among its many themes is the recurrence of shattered relationships, many destroyed by slavery’s indelible violence, some leading to horrific consequences. There is this exception: near the end of the novel, one character, Sixo, says of a woman:

She is a friend of my mind. She gather me, man. The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order. It's good, you know, when you got a woman who is a friend of your mind.

- Toni Morrison, Beloved, p. 321

A friend of [my] mind: I thought of having this stitched on a pillow for Susan’s therapy couch I’d sat on for so many years. It felt remarkable to be seen through someone else's vision, to see the pieces of myself reassembled into a picture that looked very different from the one I had held for so many years.

For the past two decades I’ve allowed myself to believe in the strength of my mind but anxiety, though less intense, still hovers. What haunts me now is the fear that I might let my mind get stale, might let myself feel that I’ve arrived at a comfort zone and can back off my craving for what I have yet to discover. I still want to actively pursue someone’s original take on issues in mental health or spiritual devotion or political courage. I want to find some new author or subject or conversational companion, some new friend to my mind to nudge me beyond my current boundaries. I want to immerse myself in some new intellectual turbulence.

I'm also painfully aware that I’m nearly 84 years old and that my memory is slipping. No, it’s not MCI (Mild Cognitive Impairment) nor dementia; I have friends who are slipping into these pre-Alzheimer’s conditions, but I’m not there, at least not yet. My doctors confirm this blessed assessment. But the threat ignites yet another level of my ancient anxiety and adds to my drive to get up early and stay up late to keep my mind fresh.

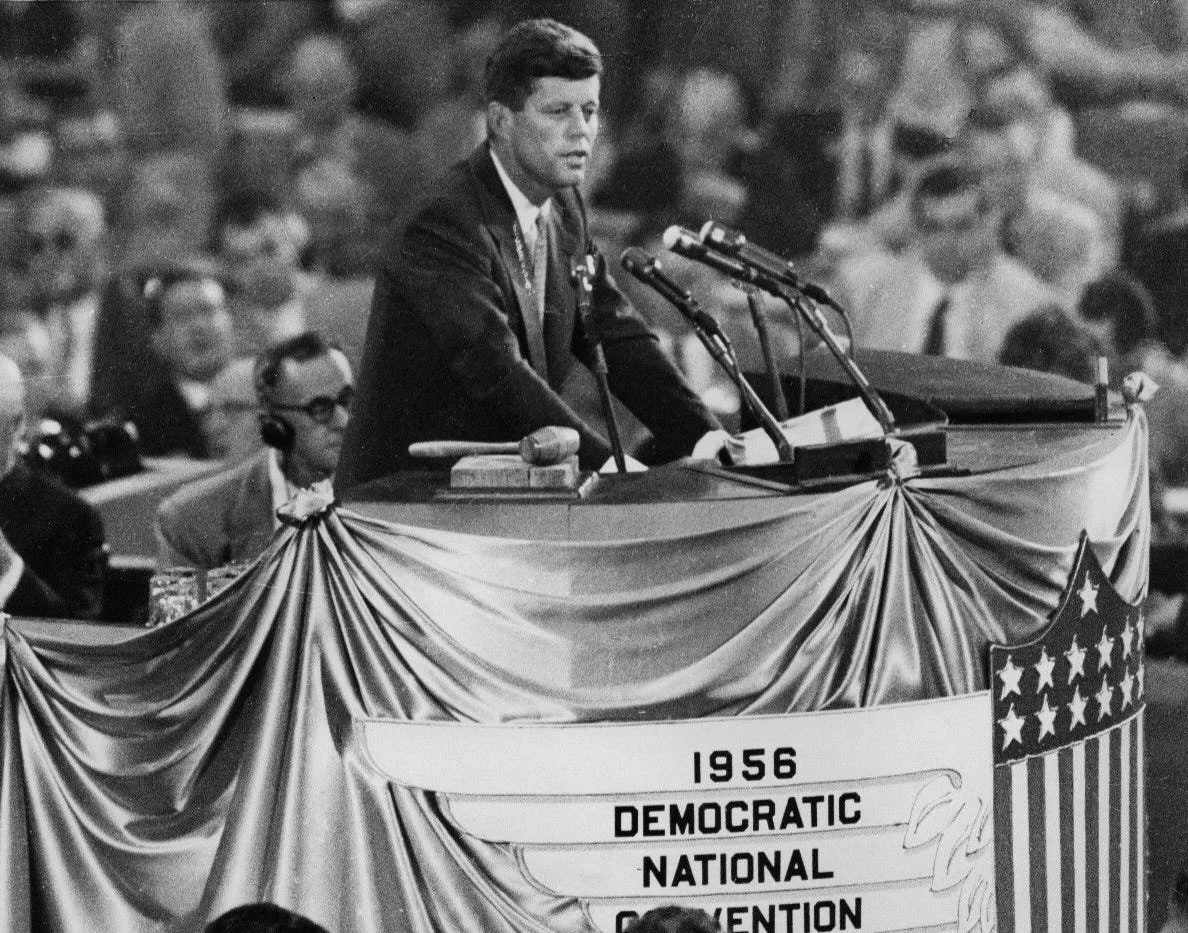

This lifelong anxiety of not being smart enough, educated enough, sophisticated enough has followed me for as long as I can remember. I recall very clearly being a junior in college, living at home with my family in Hollywood and commuting to UCLA, experiencing daily that sharp contrast between the world I came from and the one I was trying to assimilate myself into. I was one of the first people in my extended family to go from high school directly into college, and it made my mother unreasonably proud of me, which gave me the impossible task of proving to myself I was worthy of her pride. I came home one afternoon, pushed open the front door and found her sitting with her brother Jack and his wife Patricia, my aunt and uncle. I had enough hair then to brush it across my forehead, unintentionally mimicking the recently elected and already adored President Kennedy. As I entered the room, my gleeful mother started loudly humming Hail to the Chief: Bum bum ba bum bum, ba bum ba bum ba bum bum. I should have known in that moment that any clearheaded vision of myself was doomed: she believed wholeheartedly that I was exceptional while it was then exceedingly clear to me that I was not.

That ever present tension with my mother was salt in the wound: having to manage my mother's constant belief in my perfection and my own anxiety about my shortcomings made a challenging situation even more difficult, not least because it was my job to handle not just my own anxieties but hers, too. There was no space for me to voice a concern or a fear because it would turn immediately into a need to reassure and comfort her. Unlike my mother, Susan would later know the broken places in me as well as my strengths. She was the guide who walked with me out of the persistent conflict between my expectations and my realities, helped me reconcile the fantasy of being exceptional with the truth of the ordinary person I am. We found a way together for me to be a pretty good person, not a paragon of anything, but simply a successful and decent human being.

I’m confident now that I know my weakness and strengths well enough to recognize them as the truth about me. I’m aware of my persistent nemesis, my powerful impulses, in conflict with my craving for fresh ideas, the constant possibility of being distracted by my impulses toward some shiny charm that won’t help me enjoy the internal home I now live in. I’ve spent so much time and effort introspectively that I’ve finally made friends with my inner world. I know my emotions well, I’m friends with the strengths and limitations of my intellect and the realities of my aging body. I finally feel at home in my pretty good mind. I could stitch on a pillow about myself what Sixo said of his friend: It's good, you know, when you [finally become] a friend of your mind.