I've been thinking about a friend of my mind.

In the winter of 1959, our high school basketball team made it to the Los Angeles High School All-City Championship Tournament. In the first round we faced Jefferson High School, a perennial championship contender. To everyone’s surprise, we were down by a point and had the ball with seconds left when our best player was open with a jump shot from the corner. He took it, and missed: it bounced off the rim and out, the horn sounded to end the game and, exhausted, we shuffled to our bench.

Slouched with my teammates, I suddenly burst into tears, escalating into full-blown snot-nosed sobbing, repeatedly shouting No, no, no! Teammates, our couch, and our fans behind the bench went silent, staring, as I continued to sob and shout until I had emptied my emotions and wiped my wet face with my sweat-soaked jersey. To me it felt like hours; it was probably all of thirty seconds. Once I’d composed myself, no one said a word to me about my coming undone.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

For decades I’ve looked back at that moment and wished someone – our coach, a parent, a teammate – had wrapped an arm around me in comfort and helped me manage that moment with my intense, unruly emotions.

Because I definitely needed help. It wasn’t until my mid-thirties, when that same emotional intensity upended my life that someone did put an arm around me, did recommend what turned out to be the first of several therapists and the beginning of a process that would reshape who I understood myself to be.

Cliff startled me in our third or fourth session by saying, For someone with an anxiety disorder, you’re doing remarkably well. Me? With an anxiety disorder? You must be joking. The assessment took me weeks to absorb and accept, but when I finally wrapped my mind around it, I saw something new inside the intensity of my emotional make-up: at my core, I was indeed highly anxious. I discovered with him that this anxiety not only dominated my emotional life; I was also intensely anxious intellectually. I had always been desperate to learn whatever would gain the approval of my wisest friends. I scrambled to escape the lingering fear that I was like my Depression Era parents, who both curtailed their high-school educations to go to work for food and rent money. I read and studied insatiably to be in any conversation to soothe my fear that I would feel shallow and that I would be reduced to silence to cover up for what I didn’t know.

I worked with Cliff for two years, during which I took the first steps toward organizing my emotions and intellectual curiosity into a safer, saner sense of myself. As my emotions once again swelled up in me, I inevitably did or said something that created a mess I later had to clean up. I’d overwhelm our kids when they were little by barking loudly at them, or I’d embrace a new friend with an exuberance they weren’t expecting and found awkward.

If I could recognize my emotions and manage my impulses, I realized, I could keep my head above water instead of being rolled by the waves of emotion that rose up in my marriage, with my kids, and with close friends. As I learned to manage my intensity it turned out that I had large capacities for empathy and kindness that drew people to me. When calm, I was a sensitive listener and wise counsellor. Anxiety at bay!

Eventually, Cliff and I had our final session and I thanked him for his help. But as it turned out, I was not quite a strong enough swimmer to outpace my own turbulent tides.

Three years of trying on my own came to an end when one of those waves – my anxiety in a tsunami – washed over me and left me without a career and years of repair work to do with my family.

That’s when I met Susan, the therapist who saw me through my forties and fifties. I saw her once, twice, even three times a week throughout those years. Initially, my project was to coax her into believing I was the stable person I so wanted to be, despite plain evidence to the contrary. I used every persuasive trick I knew to avoid the obvious mess inside me and to win her over with my considerable charm and eloquence. None of it worked, of course.

I had spent a lifetime impressing others with my gregarious, imaginative self. I was likeable and witty, and it drew people toward me. But not Susan. She wasn’t buying any of it, wasn’t captivated by my likeableness or wit, nor interested in helping me improve these traits. She was focused not on how I presented myself to others, including her, but on that part of me that felt so intensely - the teenager who sobbed on a bench after a basketball game.

She said to me hundreds, maybe thousands of times in silent pauses, What are you thinking, Rick? She wanted to know me from the inside out. What are you thinking? How does that feel?

She was interested in the me that thought and felt intensely, the me that might detach myself from the expectations others had for me, the me that was the product of organizing the intense mess in me into a coherent, competent human being. She made it our task to discover and develop in me the skills to do this internal organizing, to shape my enormous feelings and overwhelming thoughts into something steadier.

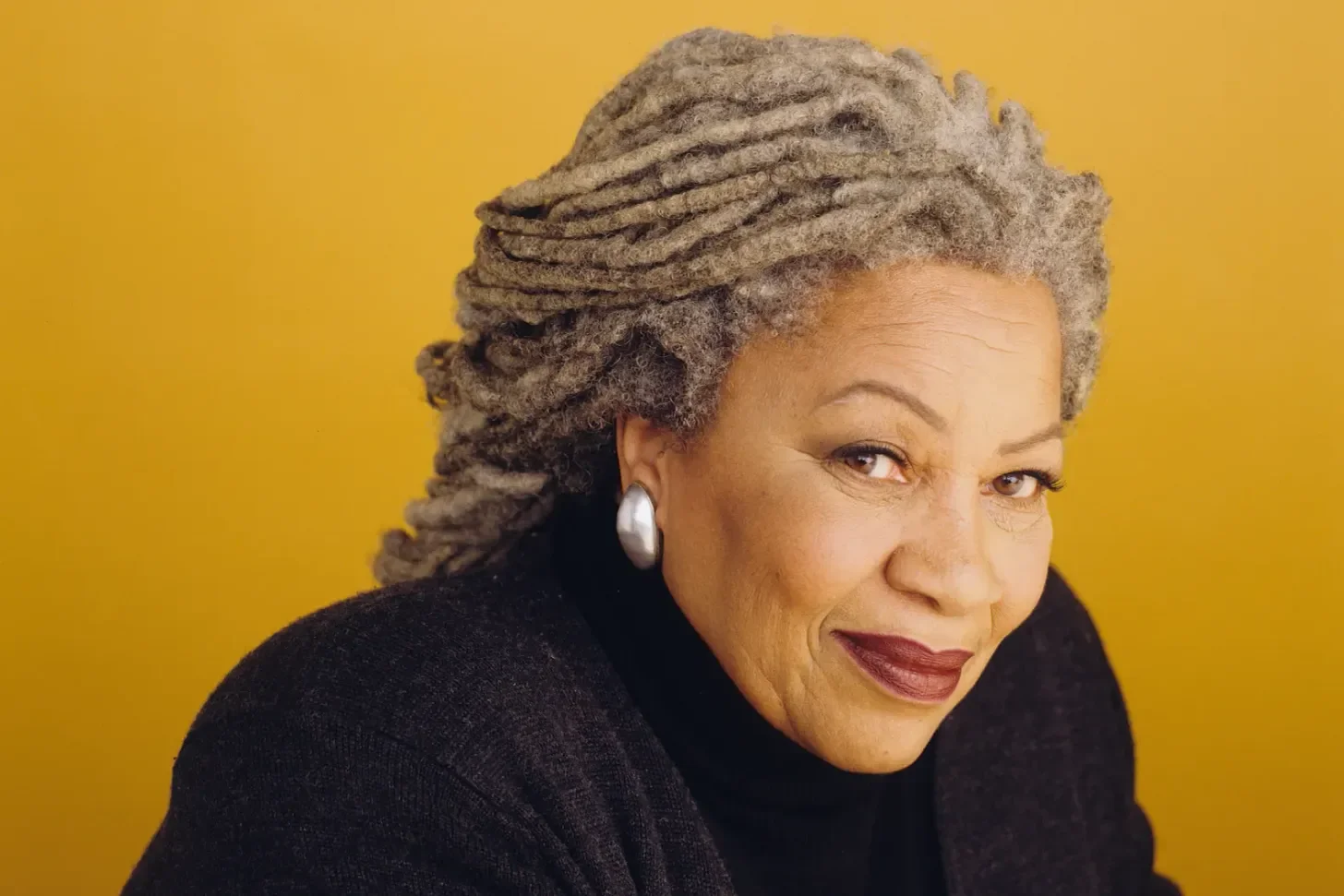

She maintained such a clear boundary between us that she never so much as shook hands with me. When she got married during our time together, she didn’t tell me; I found out from a mutual friend. Near the end of our years together I read Toni Morrison’s 1987 Pulitzer Prize winning novel, Beloved. At the end of the story a man says this about a woman in his life:

“She is a friend of my mind. She gather me, man. The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order. It’s good, you know, when you got a woman who is a friend of your mind.”

– Toni Morrison, BELOVED, p.321.

Deborah Feingold/Corbis/Getty Images

Susan became a friend of my mind by teaching me to understand myself as neither wonderful nor horrible. She helped me organize my sense of self. The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order. Late in our years together came a real test: I navigated an emotional wave that would have swamped me in prior years, and avoided a possible threat to my well-being by making the thoughtful, self-caring choice.

I described this sequence of events to Susan and concluded by saying, “You know, Susan, I’m learning how to survive.” She shot back with clear certainty, “Rick, you’re not surviving, you’re thriving.” It had been decades since I’d had such a thought about myself.

We said goodbye to one another a few years later, around the turn of the millennium. I saw her about ten years later in a restaurant, waiting alone for her lunch guest. I walked over and said “Hi.” After she smiled and said “Hi, it’s nice to see you,” I said, “You must know that you live in my mind every day; I’m so grateful for the way you helped me find myself.”

She nodded and said, “It was a privilege,” and I shook her hand.