I've been thinking about my intense discomfort in Black spaces.

A 2013 memorial service for Nelson Mandela at LA’s First African Methodist Episcopal church (Photo Credit: Press-Telegram)

In the mid-1990s, for personal reasons, I left the white Episcopal parish I’d been a leader in for twenty years and began attending the robust, several-thousand-member progressive First African Methodist Episcopal church near downtown Los Angeles. I had grown up loving Black Gospel music, relished the emotionally expressive environment of Black worship, and thrived on the preaching of Cecil “Chip” Murray and his staff. We waved our arms as we sang, got down on our knees on the floor with our elbows on our pew to pray. The drummer in the worship band would play a brief rat-a-tat-tat when Chip hit a high point in his sermon, and we responded to preaching moments with Amen or Preach it. All of this was very much not like the more subdued worship of white Episcopalians.

I worshipped there for five years, but never really felt like I belonged. I was a visitor in a self-contained system and as much as I enjoyed being there, I was uncomfortable with how little attention was paid to my presence.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

No pastor ever came to call. No one went out of their way to welcome me, though I was hard to miss: six-feet-four-inches, white, knowing words and harmonies to every song, waving my arms and shouting my own Amens. I was often one of only two or three white men among the eight-hundred worshippers in each service. I felt like no one cared about my religious or political views, no one asked me for money, and for the first time in a church, I wasn’t in charge of anything.

No one was unkind, no one told me I didn’t belong, but at the same time, not being attended to was a shock. Since my earliest years in Sunday School, I’d been important in the churches I belonged to. At First African Methodist Episcopal, this experience of being neglected felt almost oppressive, although of course it was very far from it. I was just used to being the center of attention and having people seek me out. I didn’t know how to initiate contact from this novel position. It was new to be the one who had to make the first move, and for five years I didn’t. Eventually I went back to the more comfortable, white Episcopal church I’d left.

As I think back on my experience, I’m startled by how badly I behaved, by how entitled I felt to other people’s time, attention, and respect. But even more, I am surprised and dismayed by the moral contradiction between my practice as a therapist and my conduct as a citizen. I have a deep empathy for my clients, but my empathy for and connection to Black people is and was numbed by fear.

For thirty years, I have immersed myself in the pain of my therapy clients. The only way I know to help them is to take up residence in their suffering to discover what’s animating their pain. I inhabit this difficult place with no explicit plan for resolving their conflict; the entire point is simply to be there with them. My hope is that over time, together, we will find a way to climb out. I’m patient, knowing that this journey cannot be rushed.

Contrast this to my own failure of courage as I keep my distance from my Black and brown neighbors. I’m afraid to enter their world. Maybe, like the people at First African Methodist Episcopal, they won’t need what I think I can do for them and aren’t interested in whatever affirmation of them I think I bring just by showing up. Will I be rejected as another white person showing up with my agenda for their progress? This fear holds me back.

Because I don’t know how to conduct myself in such circumstances, I stay in the safety of my white world. I talk to my white friends about how terrible the situation is in Black and brown communities, but always at a distance. Paralyzed by my ambivalence, I stand still because I’m unwilling to deal with the discomfort of figuring it out.

I’ve been thinking a lot about these interactions at church, because I’ve just finished a six-month class about what it means to be white. Fifty white men and women have been exploring who we are in relationship to non-white individuals and cultures. As white people, this is something we must intentionally and deliberately work on - this is our moral assignment in our evolving pluralistic culture. It doesn’t happen magically. It also doesn’t feel good. The effort to deconstruct white assumptions inside and around myself is hard and uncomfortable – and necessary. Some of what I’ve learned requires quite dramatic changes in my perception of myself.

Before the first session I saw myself as one of the good white people in dealing with race and was defensive about any idea that I participated in racism or had anything to learn - surely that was for other, less involved and educated people. After all, I’d marched with Dr. King, rallied and preached and contributed and voted in local and national moments to bear my witness. I had credentials; I was not part of the problem because I’d given so much to be part of the solution.

Dismantling that defensiveness has been an ongoing process, but as I begin to pull it apart, I now see myself not as a good or bad person but as a person living in a country where racial animus continues to define political and social structures that are visible only if you look for them and are willing to acknowledge what you see. I’m looking more closely now.

I recognize that so much of my engagement with race has been in groups of white people talking to white people about policy issues that affect non-white people. On committees and boards, I’ve labored with mostly white friends to address whatever the current expression is of racial tension in our communities. We leave a wall covered with sheets of paper full of objectives and actions, which we then revisit at our next gathering. Nothing ever really changes.

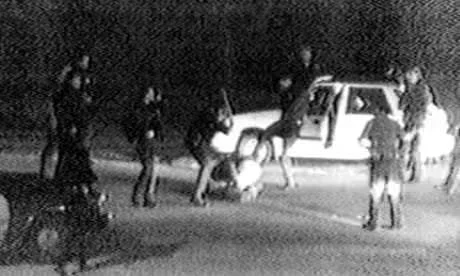

After the Los Angeles police officers who brutally beat Rodney King were acquitted in April 1992, the Black community in Los Angeles raged. I talked with white friends about the injustice of the verdict and wondered what we could do to rectify broken judicial and law-enforcement systems. But what I didn’t acknowledge to myself is that I was frightened. Media reports added insult to injury, pushing a story about the unrestrained violence of young Black men, and it worked on me. I was afraid to go to South Central, to involve myself in any way in the Black community’s tragedy. It was easier to be afraid and to think of myself as a potential victim of violence whose safety had to be the first order of business.

The police beating of Rodney King, captured on video tape by George Holliday on March 3rd, 1991. (Photograph: George Holliday/AP)

In reflecting on the choices I’ve made time and again in moments of discomfort - not real danger, which is something entirely different - it strikes me that I consistently step back, disconnect, and wait to be approached. I intellectualize problems that face real people in my city into an abstract thought exercise to be discussed with other white people.

Why is my response to the suffering of my clients so different than my response to the suffering of my neighbors? Why am I willing to wander into psychic pain, broken families, the dark shadow of a child’s death, but so unwilling to engage with the Black worshipper in the next pew? Why was it so hard for me to reach out and say hello?

I’m troubled by this moral contradiction between my convictions and my behavior. I know that the only way to participate in healing is to be present in the pain. But for fear of being foolish or uncomfortable or in some unnamable and probably imaginary danger, I keep my distance. It’s extremely unpleasant to discover that I’m pretty far from the person I believed myself to be.