I’ve been thinking about books that mattered to me in 2025.

These five books seem a more random collection than my usual favorites. They are brand new and more than a decade old; fiction and non-fiction; American stories and stories set in different cultures. And they arrived for me from sources in various parts of my reading world. Each of them is beautifully written, and the stories are compelling. I recommend each of them to you.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

Since our daughter entered high school forty years ago, I’ve read my kids and grandkids assigned books in literature. This story was from my grandson’s class last spring, and a winner of the 2012 National Book Award for Nonfiction.

Across the highway from the sparkling new airport in Mumbai, surrounded by brand new luxury hotels, is a shanty town build on mud and sewage. Boo’s story centers on a single extended family trying to crawl their way out of the muck. Abdul, the teenage son, schemes with his friends to turn trash into hope, collecting and recycling rich people’s garbage in a competitive battle that can easily turn criminal and, occasionally, violent. His mother connives to work her way into the local political structure where pots of public money might, if she’s sly enough, move her and her family into the lower middle-class. Her daughter is succeeding academically and carries the family’s hope that she’ll make her way to college and a profession that will lift all of them.

Boo spent years documenting this true story in which the hopes of this band of characters that she sketches are consistently crushed by the harsh environment and their personal choices. As I read on, the ugly discomfort of the environment and the ugly behavior of the characters subsided for me as I realized I was visiting a culture that was as much an illumination of my good fortune as a portrait of these desperate survivors.

I participated in my church’s four-month study of race, with only white people involved so we could focus on our personal histories and responsibilities around this never-ending issue. I made my way through Waking Up White as I was also reading Fever in the Heartland (read on for more on that one) and like a pendulum, my mind swung from the horror of the Klan to the painful recognition that I have my own racial reckoning to deal with.

I’ve been a liberal activist about racial issues since I was a college student in the 1960s and have been smug about my credentials: I marched with Dr. King, organized local social and political protests and projects and, when I was a pastor, preached and taught and bore my witness to the activist agenda.

What I’ve been slow to acknowledge is my place in social and economic structures that are constant, continuing obstacles to racial equality. Like Irving until she woke up, I’ve lived in white neighborhoods, gone to white schools and churches, accepted my place in a world of opportunities and advantages as if they were available to everyone. I was watching and bearing witness from outside the pain and fury of non-white communities, never embedding myself in their culture or lived experience. It’s a startling experience to recognize, in my mid-eighties, that I’ve yet to step into these worlds, yet to lean next to them in their daily plight to find opportunities and social acceptance that have been my birthright as a privileged white man. I wonder if I’ll turn this new awareness into any form of meaningful behavior.

A member of the book group I’ve been a part of for fifteen yeas recommended this novel with compelling enthusiasm. Like Boo’s Beautiful Forevers, this is Stuart’s first book, and like Boo, he was rewarded: Stuart’s novel won the 2020 Booker Prize, awarded each year for the best fiction book in the English language. Boo’s true family story is replaced here by Stuart’s fictional family mired in poverty, kept there by their mother’s self-destructive behavior.

My own mother’s ancestral roots are in Scotland, which I’ve always imagined as green highlands, rugged coasts, and ancient cities and towns where rain is as much a daily reality as the new morning. But this sad story is set in Scottish coal country and the dark dust from the shuttered mines covers every page.

At the center of the story is Shuggie, a young boy growing up outside Glasgow with his brother and sister. Early in the story, his sister moves with her new husband to South Africa and his brother abandons Shuggie and their sketchy neighborhood of welfare families for the vibrant city. What chases them from home is their mother, Agnes. She is drunk on nearly every page of this story. She uses her weekly government stipend and whatever money her absent husband gives her to buy lager and vodka to obliterate her pain. When those funds run out, she offers herself to men – friends or strangers, anyone who will pay for her services. The sex in this story is blunt in its detail, vulgar, loveless: Agnes makes herself a commodity to subsidize her addiction. Shuggie never acts out his own emerging queerness, though he is relentlessly teased and occasionally abused by other boys and men. Left alone with his mother, Shuggie devotes himself to her care. As he ages, he understands what is happening, starts to hide her stash, and caresses her to sleep with the hope that tomorrow will be different. The resolution of this story is tender but not the bright tomorrow I kept waiting for.

What lifts this story out of its coal-dust gloom is Stuart’s beautiful writing. I read with a pen in hand, and on page after page I’ve underlined phrases, sentences, and paragraphs not for their significance to the plot but for their lyrical, poetic brilliance. This is not an easy book to read but, as great books do, it took me into a world of poverty, vulgarity, and personal pain that now resides indelibly in its own corner of my mind.

Friends who grew up in the small Indiana towns central to this story recommended it, in part from their realization that the Klan had been such a force in their homeland but never mentioned in school or families as they grew up on these very sites.

Although this true story is set in Indiana and Ohio in the 1920s and 1930s, what makes it so powerful is the near-total similarity between the Klan’s ideology and practices in taking over the political, legal, and religious worlds of these midwestern states to what President Trump and MAGA are doing now. Egan’s writing is swift, clean and powerful, and the story’s concluding events are signs of hope for us in our current circumstances. This was a powerful read for me this year - so much so that I wrote a whole essay about it back in October, which you can read here:

I bought Percival Everett’s 2024 novel James when it was published because it is a reworking of Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the classic novel of America’s racial struggles which I’d read several times before. A white boy and a runaway slave float down the Mississippi, our great brown God of a river, and encounter not only a wide range of dangers but their own racially defined relationship. I read Huck again before diving into Percival’s reworking, just to have it fresh in my memory. Then James, which was an astonishment. Jim, the ignorant slave in Huckleberry Finn, is reimagined as a secretly well-educated Black man on a mission to rescue his family from a slave owner who bought them.

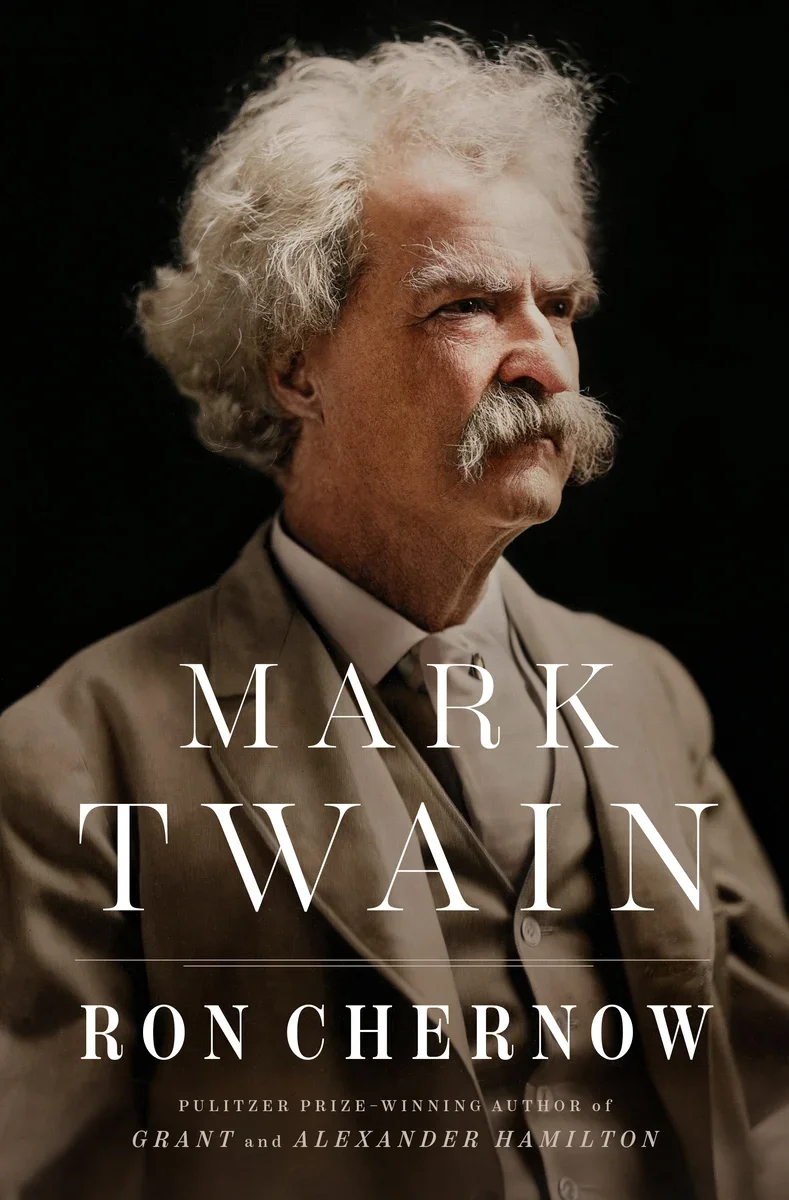

Early last summer I’d finished both books, as well as my other reading and writing responsibilities, and needed an escape. I read a review of Chernow’s new book and decided to make it my summer mental vacation. If I’d only known!

The book is 1033 pages, by far the longest book I’ve read since War and Peace. There is hardly a day in Twain’s long life unaccounted for, from his 1835 birth as Samuel Clemens in Missouri to his death in 1910 in Connecticut. This geography echoes his personal transformation on race, from a southern segregationist to a New England abolitionist. His personal life was mired by tragedy. His wife and two of his three daughters died as young women and although he made a great deal of money as a writer, it was only near the end of his life that he got his spending under control.

Embedded in this personal drama is his lasting gift to us: his writing. Twain began working for newspapers but made his lasting impact when he turned to fiction. So original was his narrative style that the novelist Ernest Hemingway claimed “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.”

Up to that point, the style and structure of fiction had largely been set by British writers and their American heirs. Twain abandoned that for a language that was colloquially and uniquely American: boys and enslaved people and the vagabonds they met did not speak proper English and their stories didn’t fit into a formal structure. It was more like floating down a river.

Once he achieved his well-deserved literary fame, Twain lectured and entertained through the last decades of his life and became one of the most recognizable figures in American culture, with his white suit, walrus mustache, and explosion of white hair. Chernow’s exhaustive tribute is worth the effort to come to know this truly original American character.