I’ve been thinking about death and dying.

Our older grandson is a student at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. On Saturday, December 13th we got a text from his parents assuring us that he was safe during the shooting in a science building there. Two students were killed, nine others injured, but he was safely locked down with his roommates, as was his girlfriend with hers.

Brown University, Photo Credit: U.S. News

We immediately turned on the television news and I could feel my heart racing; anxiety, my lifelong emotional default position, kicked in and stayed elevated for several hours as I watched the repetitious video clips, listening to Brown students describe their own traumatic experiences, working to control my breathing. Final exams were cancelled, so he flew home to Pasadena late Monday night on the 15th. I could finally exhale.

There’s a cultural script to move on, not discuss, and sweep under the rug the emotional and moral consequences of tragedies like these - both the fallout in our own individual lives and the impact in our larger shared community. But that’s never been my approach, and in the weeks that followed the incident at Brown, I started thinking about my own long, unfinished history with tragic deaths.

BECOME A FREE SUBSCRIBER TO I’VE BEEN THINKING

In 1970, when I was a thirty-year-old associate pastor in a large Presbyterian church in San Marino, California, a young woman in our church youth program was crowned high school homecoming queen. Leslie was bright, beautiful, warm hearted – the entire town celebrated her selection. Two weeks later, after a fight with her boyfriend, she took a handful of pills from the family medicine chest and soon after collapsed. I spent four days and nights in the hospital with her mother and sister, hoping, praying, fighting off fear as she sank deeper into a coma.

Our own daughter Shannon was three years old at the time, and I’d come home from the hospital, wrap my arms around her as she sat on my lap, and cry at the thought of losing Leslie and her. Fifty years later, this memory is still so vivid; it was the first time I’d been part of a slow, tragic death, and the process leaked into my bones.

I was in the emergency waiting room when the doctor came to say she’d died. Mom shouted, threw a shoe that echoed down the linoleum hallway floor, refused comfort and brooded morosely through the days between her daughter’s death and the memorial service.

The town’s collective delight plunged into terrified grief. Several hundred people, many of them frightened parents clinging to their own teenagers, jammed the sanctuary for her memorial service, and it was my role to lead them through a service that might lend comfort or at least some relief from their searing pain. I knew I was not up to the task. I couldn’t wrap my head around the tragedy, couldn’t find thoughts and words that made enough sense to me, let alone to the traumatized mourners.

After the burial that afternoon I went home, put Shannon on my lap and cried again. Five and a half decades after her death, there is still a pocket of unfinished grief in me about the death of this beautiful girl.

A few years later, my close friend John died at forty-three of a sudden brain aneurysm three days after we’d played our usual Friday tennis doubles. He was five years older than I, a PhD psychologist, Episcopal priest, husband, and father of two teenage children. His death jammed my face into my own mortality, something I’d given little thought to since I was not yet forty years old.

I gave one of the eulogies in his Episcopal parish but knew again what I’d realized a few years prior: I could not wrap my head around the impact of his death on me. If he was old enough to die, I knew for the first time that I was not immune, and I couldn’t conjure up clear thoughts about my own death. I didn’t know what to do with those thoughts and feelings.

There were others: a one-year-old boy diagnosed with brain cancer whom we prayed for until he died when he was ten; our beloved brother-in-law who taught our family how to love each other and died at fifty-four in the recovery room following open heart surgery; a middle-aged divorced friend who lived alone and never saw the lethal melanoma that grew in the middle of his back.

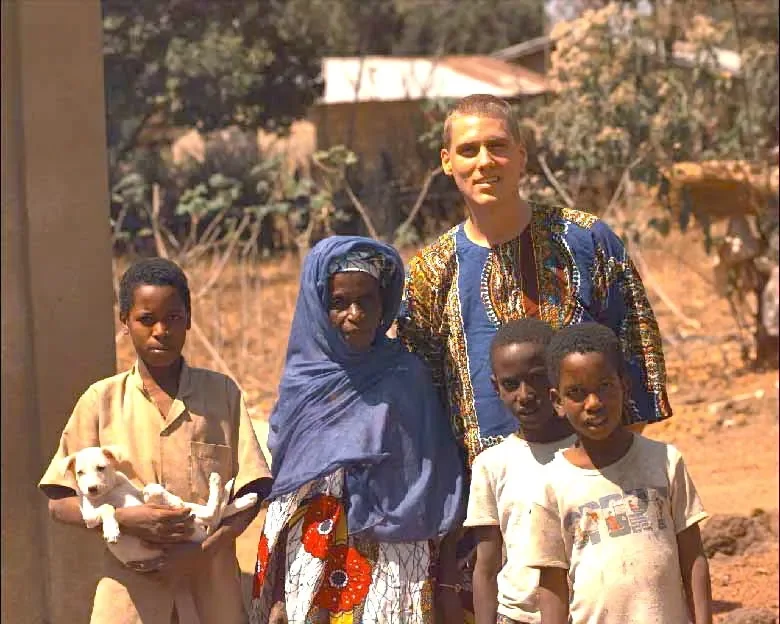

Then the worst: on January 7th, 2000, our younger son died in a terrible car accident while serving in the Peace Corps in West Africa. I cried every day for a year, flailing as I tried unsuccessfully to find some meaning in his death. I found none. I finally decided he died from a stupid accident: that’s all the meaning I could find. It’s been twenty-six years, and day by day, I carry our son in my heart. I cry now only when I hear his favorite songs, or someone catches me off guard with a new story about him.

But my grief for him lives in that crowded space where tragic deaths have a permanent home. I don’t feel or think about these losses often, but when a text arrives saying our grandson is safe in a murder scene, the ghosts rattle and scream and my anxiety and rage are once again inflamed.

As unsatisfied as I am about the meaning of these tragic deaths, I’ve learned one thing that presses itself upon me. Avoidance is impossible when losses live in me; I want to talk and listen honestly in any conversation about death and dying, whether tragic or the natural consequences of age or illness. And I’ve come around to the belief that telling the truth about death and dying also means being honest about my own mortality.

I’m growing old. In June I’ll celebrate (or at least acknowledge) my eighty-fifth birthday. I’m not as strong as I was last year; I need our son and son-in-law to lift or carry or take from a high shelf what used to be my responsibilities. My sore back now hinders my mobility and needs steroid injections to relieve chronic pain. An electrical short in my heart creates unexpected rapid heartbeats called tachycardia, which I monitor with frequent EKGs and echocardiograms. To date, I sense no mental decline beyond occasionally forgetting names, places, and where I left my damned glasses. I have no choice about being old and living with these limitations – the calendar dictates.

I’ve chosen to deal with death and dying and my unfinished grief by talking about it. Our close friends are accustomed to me referring to our son’s death by telling stories about him, and sharing with you is another way through which I breathe life into my memories of him and the others locked in that grief-filled sacred space in my soul. This storytelling has provided me a way to deal with enduring sadness and rage about tragedies that have never been resolved in my consciousness.

Talking and writing about death and dying is my strategy for dealing with this unfinished pain, but it isn’t necessarily everyone’s. We live in a culture that is uncomfortable with grief, and we lack cultural scripts or practices to hold space for it. People would rather hear that we are doing just fine, thanks, than that we’re haunted by deaths recent and remote that rise up unexpectedly.